PlatON Consensus Solution

Summary#

We propose a concurrent Byzantine fault tolerance protocol (CBFT) to solve the efficiency problem of partially synchronous networks. This article analyzes consensus protocols such as PBFT, Tendermint, and Hotstuff. With reference to their best practices, CBFT designed pipeline validation, batch production, and low-complexity view-change to improve consensus efficiency.

Distributed network model#

According to the distributed system theory, the network model of the distributed system is divided into three categories:

Synchronous network model: messages sent by nodes will definitely reach the target node within a certain time

Asynchronous network model: messages sent by nodes cannot be sure to reach the target node

Partial synchronous network model: messages sent by nodes, although delayed, will eventually reach the target node

The synchronous network model is a very ideal situation, and the asynchronous network model is closer to the actual model, but according to the principle of FLP Impossibility [1], under the assumption of the asynchronous network model, the consensus algorithm cannot simultaneously satisfy the security safety and liveness, most current BFT consensus algorithms are based on the assumption of a partially synchronous network model. We also discuss based on the assumption of a partially synchronous network model.

BFT consensus protocol#

BFT Protocol Overview#

A distributed system is composed of multiple nodes, and the nodes need to send messages to communicate with each other. According to the protocol they follow, consensus is reached on a certain task message and is executed consistently. There are many types of errors in this process, but they can basically be divided into two categories.

The first type of error is node crash, network failure, packet loss, etc. This type of error node is not malicious and belongs to non-Byzantine error.

The second type of error is that the node may be malicious and does not follow the protocol rules. For example, the validator can delay or reject messages in the network, the proposer can propose invalid blocks, or the node can send different messages to different peers. In the worst case, malicious nodes may cooperate with each other. These are called Byzantine errors.

Considering these two errors, we hope that the system can always maintain two attributes: safety and liveness.

- Security: When the above two types of errors occur, the consensus system cannot produce wrong results. In the semantics of blockchain, it means that there will be no double-spending and forks.

- Liveness: The system has been able to continuously generate submissions. Under the semantics of the blockchain, it means that consensus will continue and will not get stuck. If the consensus of a blockchain system is stuck at a certain height, then the new transaction is not responding, that is, it does not meet the liveness.

Byzantine Fault Tolerance Protocol (BFT) is a protocol that can guarantee the security and activity of distributed systems even if malicious nodes exist in the system. According to the classic paper of Lampport [2], all BFT protocols have a basic assumption: when the total number of nodes is greater than 3f, the maximum number of malicious nodes is f, and honest nodes can reach a correct result that is consistent.

PBFT#

The practical Byzantine fault tolerance algorithm (PBFT [3]) is one of the first Byzantine fault tolerance protocols in the real world to be able to handle the first and second types of errors at the same time. Based on the partial synchronization model, it solves the problem of low efficiency of previous BFT algorithms by reducing the complexity of the algorithm from the exponential order of the number of nodes to the square order of the number of nodes, the Byzantine fault tolerance algorithm becomes feasible in practical system applications.

The BFT consensus protocols currently used in blockchains can be considered as a variant of PBFT, which is in the same vein as PBFT.

Normal process#

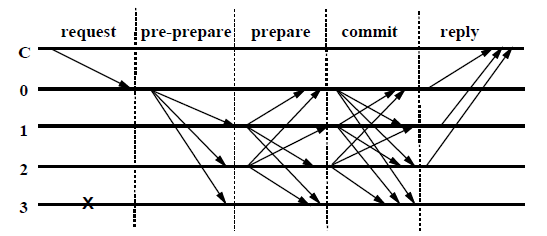

The normal PBFT process is shown below (C is the client in Figure 1, the system has four nodes numbered 0 to 3, and node 3 is a Byzantine node):

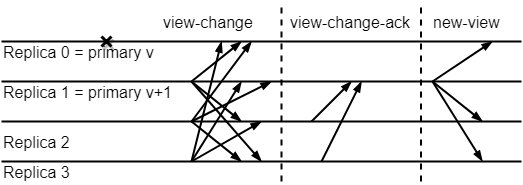

View switching process#

view-change is the most critical design of PBFT. When the master node hangs (no response after timeout) or the replica node collectively thinks that the master node is a problem node, the view-change will be triggered. At this time, the nodes in the system broadcast the view-change request, and when a node receives enough view-change requests, it will send a view-change confirmation to the new master node. When the new master node receives enough view-change confirmations to start the next view, each view-change request must include a message that the node has reached the prepared state sequence number.

During the view-change process, we need to ensure that the sequence number of the submitted message is also consistent throughout the view-change. In simple terms, when a message is sequenced n and 2f + 1 prepare messages are received, it will still be assigned a sequence number n in the next view and restart the normal process.

Communication complexity#

PBFT is an agreement based on a three-phase voting process. In the prepare and commit phases, each node needs to broadcast its own prepare or commit message, so the communication complexity is $$ O(n^2) $$.

During the view-change process, all replica nodes are required to time out first, and then a consensus is reached on view-change. Then, they let the new master node know about the reached consensus. The new master node will broadcast this message to announce view-change, so the communication complexity of view-change is $$O(n^3)$$.

The communication complexity of up to $$O(n^3)$$ undoubtedly has a serious impact on the consensus efficiency of PBFT, which greatly limits the scalability of PBFT.

Optimization of BFT protocol#

How to reduce the communication complexity of $$O(n^3)$$ to $$O(n)$$ and improve the efficiency of consensus is the challenge that the blockchain BFT consensus protocol faces. There are several approaches to optimize BFT consensus efficiency:

Aggregation signature#

E. Kokoris-Kogias et al. proposed in their paper the method of using aggregate signatures in the consensus mechanism. The ByzCoin [4] mentioned in the paper replaced the original MAC used by PBFT with a digital signature to reduce the communication delay from $$O(n^2)$$ to $$O(n)$$. The communication complexity is further reduced to $$O(logn)$$. But ByzCoin still has limitations in terms of malicious master node or 33% fault tolerance.

After that, some public chain projects, such as Zilliqa [5], etc., based on this idea, adopted the EC-Schnorr multi-signature algorithm to improve the message passing efficiency in the Prepare and Commit stages of the PBFT process.

Communication mechanism optimization#

PBFT uses all-to-all messages that creates $O(n)$ communication complexity.

SBFT (Scale optimized PBFT) [6] proposed a linear communication mode using a collector. In this mode, the message is no longer sent to each node, but to the collector, and then broadcasted by the collector to all nodes. Further more, the message length can be reduced from linear to constant by using threshold signatures, which reduces the total overhead to $$O(n)$$.

Tendermint [7] uses a gossip all-to-all mechanism, so $$O(nlogn)$$ messages and $$O(n)$$ words under optimistic conditions.

view-change process optimization#

All BFT protocols change the master node through view-change. Protocols such as PBFT and SBFT have independent view-change processes, which are triggered when there is a problem with the master node. In Tendermint, HostStuff [8] and other protocols, there is no explicit view-change process. The view-change process is integrated into the normal process, so the efficiency of view-change is improved, and the communication complexity of view-change is reduced.

Tendermint integrates round-change (similar to view-change) into the normal process, so round-change is the same as the normal block message commit process. There is no separate view-change process like PBFT, so the communication complexity is reduced to $$ O(n^2) $$.

HotStuff refers to Tendermint and also merges the view-change process with the normal process, that is, there is no longer a separate view-change process. By introducing a two-stage voting lock, and adopting a leader node set BLS aggregation signature, the communication complexity of view-change is reduced to $$ O(n) $$.

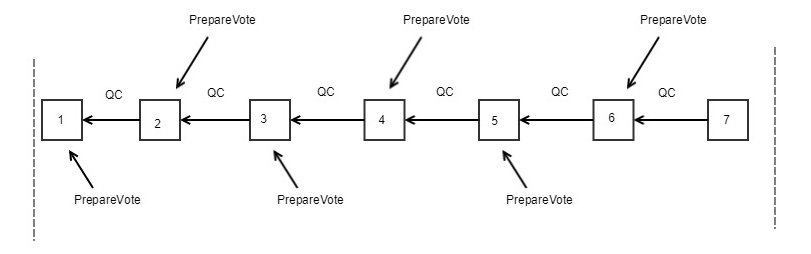

Chained BFT#

Traditional BFT requires two rounds of consensus for each block. The communication complexity of $$ O(n) $$ can make the block reach prepareQC, but the communication complexity of $$O(n^2)$$ is required for the block to reach commitQC.

Hotstuff changed the two-round synchronous BFT of the traditional BFT to a three-round chain BFT. There is no clear prepare and commit consensus phase. Each block only needs to perform one round of QC. The prepare phase of the latter block is the previous one. The pre-commit phase of the next block is the commit phase of the previous block. Each time the block is generated, it only requires communication complexity of $$O(n)$$. Through the two rounds of communication complexity of $$O(n)$$, the previous $$O(n^2)$$ effect is achieved.

Pipelining and Concurrency#

Protocols such as PBFT and Tendermint have the characteristics of Instant Finality, and it is almost impossible to fork. In PBFT, every block has to be confirmed before the next block can be produced. Tendermint also proposes a proof-of-lock-change mechanism, which further ensures the instant certainty of the block, that is, in a round stage, nodes vote on a block with pre-commit, in the next round, the node can only vote for the same block with pre-commit, unless it receives a new proposer's unlocking certificate for a certain block message.

This type of BFT consensus protocol is essentially a synchronous system that tightly couples the production and confirmation of blocks. The next block can be produced only after previous block get confirmed. The system has to wait for the longest possible network delay between blocks, and the consensus efficiency is greatly limited.

HotStuff separates the production and confirmation of blocks. The final confirmation of each block requires the latter two blocks to reach QC, which means that the next block can be produced without the previous block being fully confirmed. This method is actually a semi-synchronous system. The production of each block still needs to wait for the previous block to reach QC.

EOS [9] 's BFT-DPoS can be considered as a completely parallel pipelining solution: each block is broadcast immediately after production, and the block producers wait for 0.5 seconds to produce the new block while receiving the confirmation of the old block from other nodes. The production of the new block and the receipt of the old block are performed at the same time, which greatly optimizes the block production efficiency.

CBFT consensus protocol#

Why design CBFT#

In the previous content, we analyzed the problems of the BFT consensus protocol and several mainstream optimized BFT consensus protocols. These BFT consensus protocols have achieved good research results in reducing communication complexity and block production efficiency, but there are still some room for improvement.

Compared to previous BFT, Although PBFT is more practical, due to the view-change overhead of $$O(n^3)$$, there is a big problem in scalability.

Tendermint merges round change with normal processes, simplifies view-change logic, and reduces the communication complexity of view-change to $$ O(n^2) $$, but needs to wait for a relatively large network delay to ensure activity. Further more, Tendermint is still serially producing and confirming blocks.

In EOS's BFT-DPOS consensus protocol, block producers can continuously produce several blocks, and the blocks are confirmed in parallel, which increases the block production speed. The block is confirmed using the BFT protocol, but only suitable for strong synchronized communication model.

HotStuff innovatively proposed a three-phase submission BFT consensus protocol based on the leader node, absorbing the advantages of Tendermint, merging view-change with normal processes, and reducing the communication complexity of view-change to linear. By simplifying the message type, the block can be confirmed in a pipeline manner. However, the introduction of a new voting stage will also increase the communication complexity. In addition, a view window only confirms one block. This undoubtedly requires more communication complexity in view-change. In addition, the star-like topology based on the collection of votes by leader nodes is more suitable for a good alliance chain such as Libra. In a weak network environment, it is more likely to be affected by a single point of failure, resulting in a large leader node switching overhead.

Therefore, we proposed the CBFT consensus protocol. Further optimization on top of the above consensus protocol can dramatically reduce the complexity of communication and improve the efficiency of block production.

CBFT Overview#

Based on the partially synchronous mesh communication model, CBFT proposed a three-phase consensus concurrent Byzantine fault tolerance protocol. The mesh communication model is more suitable for the weak network environment of the public network.

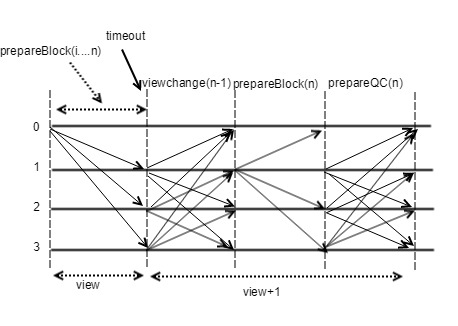

The normal process of CBFT is similar to Hotstuff, and it is divided into prepare, pre-comit, commit, and decide stages. However, CBFT has also made key improvements: batch blocks can be proposed in a view window continuously, and the production of the next block does not need to wait for the previous block to reach QC; block producer can product the next block in parallel while receiving the vote of the previous block, which greatly improves the block production speed.

CBFT has a self-adaptive view-change mechanism: in a view window, when a node receives enough blocks and votes in favor (more than 2/3 of the nodes vote, that is, QC), it will automatically switch to the next view, no view-change vote required. Otherwise, the node will start the view-change process which can be completed within the communication complexity of $$ O(n^2) $$ by using the Hotstuff-like two-stage lock rules and BLS aggregation signatures.

In normal network environment, CBFT will not trigger a view-change unless extreme network exception, so it will have less view-change overhead than HotStuff.

Next, the related concepts and meanings involved in the CBFT consensus will be given first, the CBFT details will be introduced later.

CBFT related terms#

- Proposer: The node responsible for generating blocks in the CBFT consensus

- T: Time window, each proposer can only make blocks in his own time window

- N: Total number of consensus nodes

- f: maximum number of Byzantine nodes

- Sufficient enough votes: indicates that at least N-f votes have been received

- Validator: Non-proposer node in consensus node

- View: The time range of the current proposal's time window can generate blocks

- ViewNumber: The serial number of each time window, increasing with time window

- HighestQCBlock: Local highest N-f PrepareVote block

- ProposalIndex: The index number of the proposer

- ValidatorIndex: Validator's index number

- PrepareBlock: Proposed block message, which mainly includes Block, the index number of the proposer

- PrepareVote: Validators vote for the Prepare of the proposed block, and each validator needs to execute the block before sending PrepareVote. Mainly include ViewNumber, block hash, block height, validator index number (ValidatorIndex)

- view-change: When the time window expires and the proposer's blocks have not all collected N-f PrepareVote, then the next proposer will send view-change. view-change contains the index number of the proposer (ValidatorIndex), the highest confirmation block (HighestQCBlock)

- Lock: Lock the specified block height

- Timeout: Timeout (time window expiration can be considered as the timeout time of the proposer)

- Legal: Maximum allowed

- One View: The ViewNumbers of two Views are equal and can be the same View

BLS Signature#

Currently, the aggregate signature scheme adopted by the industry is BLS aggregate signature. BLS aggregation signature is an extension scheme based on BLS signature scheme. The Boneh-Lynn-Shacham (BLS) signature scheme was proposed by Dan Boneh, Ben Lynn, Hovav Shacham [10] in 2001. BLS signatures are currently used in many blockchain projects such as Dfifinity, fifilecoin, and Libra. The BLS aggregate signature can simplify multiple signatures into one aggregate signature, which is very important for improving the communication efficiency in the BFT consensus protocol.

It is worth noting that the method of BLS aggregation signature has defects. An attack called rogue public key can give the attacker the opportunity to manipulate the output of the aggregate signature after obtaining the public keys of other signers and standard BLS signature information.

One of the most direct defenses against this attack is that everyone participating in the BLS aggregate signature needs to first prove that they actually have the BLS private key information and register in advance. This process can be accomplished by using a simple and efficient zero-knowledge proof technology (Schnorr non-interactive zero-knowledge proof protocol). Participants need to give zero-knowledge proofs before they perform aggregate signatures to prove that they hold the public key information, and indeed they have the private key information corresponding to the public key.

CBFT protocol flow#

Normal process#

Verify blocks one by one: The validators verify the signature and time window, executes the block, and generates PrepareVote <ViewNumber, BlockHash, BlockNumber> after success. When N-f PrepareVote is collected by the parent block corresponding to PrepareVote, the individual signatures of N-f PrepareVote are aggregated into one aggregate signature using BLS, and broadcast the current PrepareVote. We simplify N-f PrepareVote(s) to one prepareQC (quorum certificate).

When the node receives prepareQC in the last block in the current view, it will enter the new view and start the next round of voting.

In order to vote more securely, voting must comply with the following rules:

Vote after block execution

Honest nodes can only vote on the blocks proposed by the current View

When current view times out, honest nodes can no longer vote, and will not receive votes from the current View

If there are two blocks with same height in one view, can only vote for one of them

When voting on Block (n + 1), Block (n) must reach prepareQC

view-change Process#

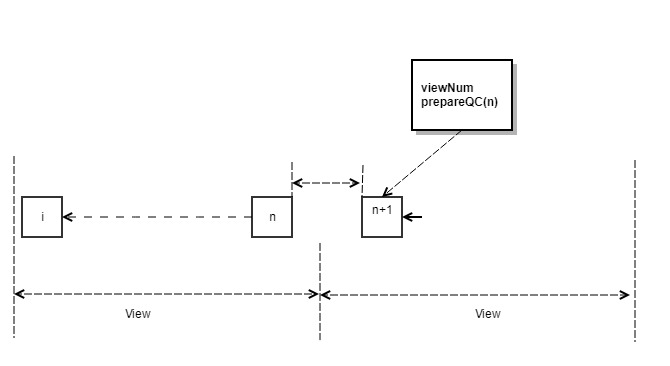

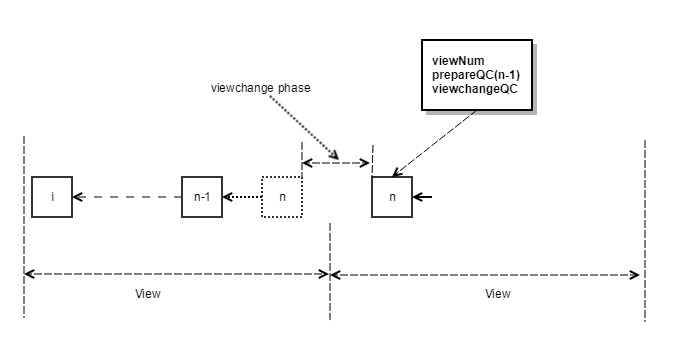

- If within the time window, the block n prepareQC is received, the local view + 1 is updated to enter the new normal process. In this case, if the new proposer reaches the QC of n, the first block of new view is broadcasted. The block, as shown in Figure 4, has a BlockNumber (n) +1 height and will carry a prepareQC for block n.

- If the time window expires, the node will first refuse to generate a new vote for the block of the current proposer, and at the same time does not receive the prepareQC of the block n, it sends a view-change <ViewNumber, HighestQCBlock> message, as shown in Figure 5.

- After the proposer of the next time window received N-f view-change messages (we refer to N-f view-change messages as viewchangeQC), it uses the BLS signature to aggregate into a QC signature, and then update the local ViewNumber + 1. Based on the two stage voting lock mechanism, the new proposer can simply select HighestQCBlock from the N-f view-change messages received, set the new block number to HighestQCBlock + 1, as shown in Figure 6, and then broadcast the first block to each validator node together with the QC signature of HighestQCBlock and the QC signature of view-change.

- Each validator node will start a new round of consensus based on the received HighestQCBlock + 1 sequence number.

Block confirmation#

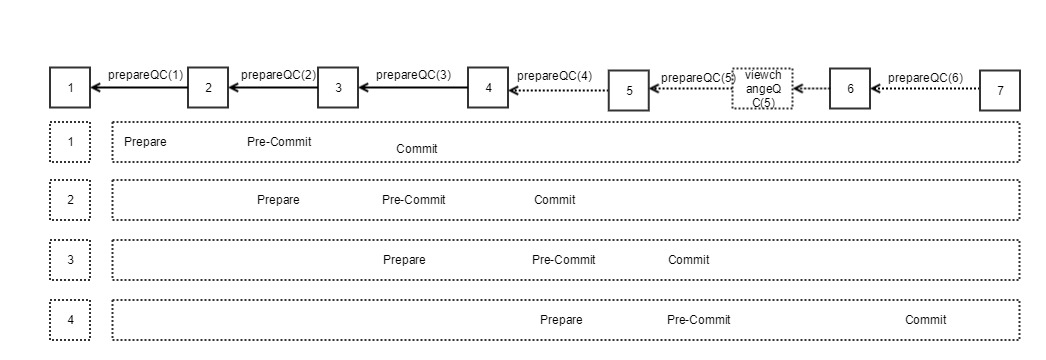

Pipelining Process#

In traditional BFT (PBFT, Tendermint), each block usually needs to go through a clear Pre-Commit and Commit phase before final confirmation:

Pre-Commit: When a node receives N-f Prepare votes, it will broadcast Pre-Commit. Pre-Commit can be considered as confirmation of the Prepare phase.

Commit: When N-f Pre-Commit votes are received, it indicates that all nodes agree on the specified message and submit it to the local disk.

In contrast, CBFT also has the two phases, Prepare and ViewChange. Each block has only Prepare vote, and has no clear Pre-Commit and Commit phase. So how to achieve block confirmation? The CBFT can be regarded as the pipeline BFT, and each prepareQC is a further confirmation of the previous block.

Therefore, in CBFT, there are only two message types: prepare message and view-change message, and the QC of each message is verified by the aggregate signature method.

Block Reorganization#

Assume each view allows $$n$$ blocks to be generated. The current view $$ V_i $$ time window expires and the view switches to $$ V_ {i+1} $$. At this time, only part of blocks generated by $$ V_i $$ get QC, and some blocks will be reorganized, the reorganization rules are as follows:

Blocks reached Pre-Commit state will be locked and cannot be reorganized. That is, if the current node has a Pre-Commit state block at height h, the current node cannot generate new blocks at height h, and cannot Vote on other blocks with height h.

Blocks with Prepared state can be reorganized, that is, if the current node has a Prepared state block at height h, the current node can generate new blocks at height h, or vote for other blocks at height h (can only vote for Blocks with higher viewnumber)

Validator Replacement Mechanism#

In the CBFT consensus, the validator pool is reshuffled every 430 blocks (a.k.a Epoch). The rules are as follows:

New validators may not be able to participate in consensus due to issues such as network connection or block synchronization, so we replace no more than 14 nodes each time. If there are less than 14 candidate validators, the number of replacements is the total number of candidate validators.

Use VRF to randomly select new validators from candidate validators.

Fault Tolerance Recovery (WAL) mechanism#

The CBFT consensus provides a fault tolerance recovery mechanism, which is the WAL module. This module does not belong to the write-ahead log system in the strict sense, but it draws on the relevant ideas, and in the process of validator consensus, the consensus state of the yet-to-be-finalized block and the current View consensus message are persisted from memory to the local database and local files. After the system crashes or the machine is powered off and restarted, the consensus state is quickly restored through the disk log data.

Here is a brief introduction to the main principles:

Block, ViewChange requires consensus between each validator going through stages of verification, voting, etc. Before a block finally recorded the chain, the consensus status and messages related to the block are stored in memory. Restarting a node only needs to restore the memory data of this part of the unchained block. Therefore, the checkpoint of recovery is the currentBlock of the current blockchain.

According to voting mechanism. The voting of each block is a confirmation of the previous block, and the Commit stage of the block is reached at the third level, so the prepareQC status of 3-Chain is crucial in the consensus. This part of the data is stored in the db since it is important to ensure recovery after restarting.

The consensus messages of most recent view will be stored to a file.

Block synchronization mechanism#

Due to the asynchronous parallelism of the CBFT consensus, the latest blocks are stored in memory, and the block height has three heights: the highest logical block height, the highest confirmed block height, and the write block height, and three heights decrement in order. Therefore, the block synchronization mechanism in CBFT is also adapted on the basis of the existing ETH-P2P, and the block height acquisition method is adjusted.

Here is an overview of the block synchronization mechanism:

Newly added nodes update blocks to mainnet height via ETH-P2P with fast synchronization or full synchronization

Consensus nodes use CBFT-P2P's heartbeat mechanism to keep the block height consistent with other nodes

When the consensus node block height lags behind, it will actively reduce the communication volume and fully focus on block synchronization

Synchronization mechanism uses BLS signatures to reduce the amount of network synchronization messages

CBFT Analysis#

Basic Rule Definition#

To facilitate the analysis of the safety and activity of CBFT, we define several basic rules of CBFT.

K-Chain Rules#

For a chain, the following conditions are met:

B (0) <-C (0) <-... <-B (k-1) <-C (k-1)

We define it as K-Chain, where B(0) is Block 0 and C(0) is B(0)'s prepareQC. A 3-Chain instance is as follows: B0 <-C0 <-B1 <-C1 <-B2 <-C2, in this 3-Chain, B0 reaches the Commit state.

Lock-Block Rules#

In node a, when block n receives 2 prepareQCs after block n, block n is defined as Lock-Block (a). It can be observed that when Lock-Block (a) = B0, B0 reaches 2-Chain, such as B0 <-C0 <-B1 <-C1.

Unlock-Block Rules#

Assume Lock-Block (a) is n. When n + 1 of child block n reaches prepareQC twice, Lock-Block (a) is n + 1. It can be observed that when Lock-Block (a) = B0, B0 reaches 2-Chain, such as B0 <-C0 <-B1 <-C1-B2, when B0 Unlock-Block, B0 reaches 3-Chain, such as B0 <-C0 <-B1 <-C1 <-B2 <-C2.

Previous-Block Rule#

In the form of Block (B) <-prepareQC (B) <-Block (B '), we define Block (B) as the Previous-Block of Block (B'), which can be expressed as Previous-Block (B ') = Block (B).

From the Lock-Block and Previous-Block rules:

In node a, the form B <-C <-B '<-C' <-B '', Previous-Block (B '')> Lock-Block (a)

Commit Rule#

When block n receives 3 prepareQCs after block n, block n is Commit. It can be observed that when B0 is Commit, B0 reaches 3-Chain, such as B0 <-C0 <-B1 <-C1 <-B2 <-C2.

Proof of Safety#

1) There will be no two blocks of the same height in the same View can receive enough votes

Proof: Assuming N = 3f + 1 is the total number of nodes and f is the maximum number of Byzantine nodes, then when 2f + 1 votes are received, they are enough votes. Since both blocks received at least 2f + 1, the total number of votes was at least 2 (2f + 1) = N + f + 1. You can see that at least f + 1 voted for two blocks, which is contradict to f Byzantine nodes assumption.

2) For 3-Chain, B0 <-C0 <-B1 <-C1 <-B2 <-C2, ViewNumber (B2)> = ViewNumber (B0). Then Block (B) exists. When ViewNumber (B)> ViewNumber (B2), Previous_Block (B)> B0.

Proof: For a normal honest node (voted for block B2 and B), then the node can at least see B0 <-C0 <-B1 <-C1 <-B2, which is the minimum Lock-Block It is Lock-Block (B0). Because ViewNumber (B)> ViewNumber (B2), according to the view-change confirmation rule, the first block of ViewNumber (B) is not less than B1, then Previous_Block (B)> B0

3) Assume Lock-Block (n) = B for node n and Lock-Block (m) = B 'for node m. If Number (B) = Number (B'), then Hash (B) = Hash (B ')

Proof: From the Lock-Block rules above, we know that there are two types of Lock-Block scenarios. In the first case, two QCs are in the same view. From 1), we know that B 'and B cannot receive enough votes at the same time . In the second case, B and B 'belong to different views, and both receive prepareQC (B), prepareQC (B'). Assuming ViewNumber (B ')> ViewNumber (B), then according to conclusion 2), Previous_Block (B')> B, contradicts to the assumption.

4) During the Commit phase, there will be no two Hashes of the same height and different blocks be Committed.

Proof: From 3), if Number (B) = Number (B '), There will be no B and B' as Lock-Block at the same time. It can be deduced that there will be no Commit (B), and Commit (B’) are all both submitted.

Proof of Liveness#

Assume that the maximum network delay between nodes is T and the execution time for a block is S.

1) Time window of a view cannot be always less than time (prepareQC) * 2

Proof: Reasonably adjust the actual window length according to the actual network conditions to ensure that QC is reached at least 2 times in the time window, and the time window is at least 2 S + 4 T

2) ViewNumber can reach an agreement and increase

Proof: ViewChange requires at least T to reach agreement. Conclusion 1) can guarantee that ViewChange can reach agreement, and then ViewNumber can be incremented.

3) Lock-Block height always increases

Proof: Assuming ViewNumber is n, n + 1, the proof of safety 2) can guarantee that the first block of ViewNumber (n + 1)'s' Previous-Block is at least Lock-Block (View (n)). And because of the proof of liveness 1), there are at least two prepareQCs, and the relationship between the lock heights of the two Views can be obtained. Lock-Block (View (n + 1))> = Lock-Block (View (n)) + 1

Communication complexity analysis#

- PBFT: Mesh network topology, using a two-stage voting protocol, messages are locked when they are in the prepared state, there is a separate view-change process, the communication complexity of the normal process is $$ O(n^2) $$, and the communication complexity of the view-change process is $$ O(n^3)$$.

- Tendermint: Mesh network topology, using a two-stage voting protocol, messages are locked when they are in the prepared state, the view-change process is merged with the normal process, and the communication complexity is $$ O(n^2) $$.

- Hotstuff star network topology, using a three-phase voting protocol, the message is locked when it reaches the pre-committed state, the ViewChange process is merged with the normal process, and the communication complexity is $$O(n)$$.

- CBFT: mesh network topology, using a three-phase voting protocol, messages are locked when they reach the pre-committed state, the process of self-adaptive view-change, and the communication complexity is $$ O(n^2) $$.

Case Analysis#

This section lists some specific exception cases, and infers the cases to detect whether there are problems in safety and liveness.

Initial state#

Assume that there are four nodes A, B, C, and D, and each view has a maximum of 2 blocks. The last block is block 7 produced by D, which is in QC state in the four nodes.

The state of the last block of the four nodes is as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7(QC) | D7(QC) | D7(QC) | D7(QC) |

Network exception#

A's turn to produce blocks#

Assume that it is A's turn to produce block. A produce block 8 and 9 based on block 7. Block 8 and 9 are synchronized to B, C, and D. A receives enough PrepareVote messages for blocks 8 and 9. Block 8 and 9 reach QC state on A. However, due to network reasons, D did not receive enough PrepareVote messages for block 8, B, C and D did not receive enough PrepareVote messages for block 9. The block state of each node is as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7(QC)commit | D7(QC)lock | D7(QC)lock | D7(QC) |

| A8(QC)lock | A8(QC) | A8(QC) | A8 |

| A9(QC) | A9 | A9 | A9 |

When timeout, B, C and D will send view-change request.

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| nil | ViewChange<A8> | ViewChange<A8> | ViewChange<D7> |

B's turn to produce blocks#

As A's View ends, it's B's turn to produce blocks. B will encounter the following two situations.

B-1: B received QC of ViewChange earlier

Suppose B receives C.ViewChange <A8>, D.ViewChange <D7> before QC of A9, then B will produce B9 and B10 based on A8.

The actions of each node after receiving B9 are as follows:

A B C D Verified B9 Verified B9 Verified B9 Verified B9 Because B9's PrepareBlock message carries A8‘s prepareQC, D can confirm A8 locally. The block state of each node is as follows:

A B C D D7(QC)commit D7(QC)lock D7(QC)lock D7(QC) A8(QC)lock A8(QC) A8(QC) A8(QC) A9(QC) B9 A9 B9 A9 B9 A9 B9 B10 B10 B10 B10 B-2: B received QC of A9 earlier

Suppose B receives QC of A9 before viewchangeQC, then B will produce B10 and B11 based on A9.

Because B10‘s PrepareBlock message carries A9’s prepareQC, C can confirm A9 locally. The actions of each node after receiving B10 are as follows:

A B C D Verified B10 Verified B10 Verified B10 nil The block state of each node is as follows:

A B C D D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC) A8(QC)lock A8(QC) lock A8(QC)lock A8(QC)lock A9(QC) A9(QC) A9(QC) A9(QC) B10 B10 B10 B10 B11 B11 B11 B11

C's turn to produce blocks#

Now it's C's turn to produce blocks. The following is based on B-1. Assuming that B9 is not reached QC, there may be two cases of HighestQCBlock for each node. The view-change analysis in different cases is as follows:

The HighestQCBlock for each node is as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| A9 | A8 | A8 | A8 |

The view-change actions of each node are as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| ViewChange<A9> | ViewChange<A8> | ViewChange<A8> | ViewChange<A8> |

C will produce different blocks based on the received ViewChange message.

C-1 Suppose C receives B.ViewChange <A8>, C.ViewChange <A8>, D.ViewChange <A8>, then C will generate C9 and C10 based on A8. The actions of each node after receiving C10 are as follows:

A B C D Verified C9 Verified C9 Verified C9 Verified C9 The block state of each node is as follows:

A B C D D7(QC)commit D7(QC)lock D7(QC)lock D7(QC) A8(QC)lock A8(QC) A8(QC) A8(QC) A9(QC) B9 C9 A9 B9 C9 A9 B9 C9 A9 B9 C9 B10 C10 B10 C10 B10 C10 B10 If C9 reaches QC, the block state of each node is as follows:

A B C D D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit A8(QC)lock A8(QC)lock A8(QC)lock A8(QC)lock A9(QC) B9 C9 (QC) A9 B9 C9 (QC) A9 B9 C9 (QC) A9 B9 C9 (QC) B10 C10 B10 C10 B10 C10 B10 C-2 Suppose C receives A.ViewChange <A9>, B.ViewChange <A8>, C.ViewChange <A8>, then C will produce C10 and C11 based on A9. The actions of each node after receiving C10 are as follows:

A B C D Verified C10 Verified C10 Verified C10 nil: C10 was not received due to network reasons The block state of each node is as follows:

A B C D D7(QC)commit D7(QC)lock D7(QC)lock D7(QC)lock A8(QC)lock A8(QC) lock A8(QC) lock A8(QC) A9(QC) B9 A9(QC) B9 A9(QC) B9 A9 B9 B10 C10 B10 C10 B10 C10 B10 C11 C11 C11 C11 If C10 reaches QC, the block state of each node is as follows:

A B C D D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)lock A8(QC)commit A8(QC)commit A8(QC) commit A8(QC) A9(QC)lock A9(QC)lock A9(QC)lock A9 B9 B10 C10(QC) B10 C10(QC) B10 C10(QC) B10 C11 C11 C11 C11

Double-producing#

Suppose it is A's turn, and A is a Byzantine node. Blocks 8 and 9 are produced based on block 7. In addition, block 8 'is produced based on block 7.

The state of the last block of the four nodes is as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7(QC) | D7(QC) | D7(QC) | D7(QC) |

| A8, A8' | A8, A8' | A8, A8' | A8, A8' |

| A9 | A9 | A9 | A9 |

If A8 reaches QC

The state of the last block of the four nodes is as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7(QC) lock | D7(QC)lock | D7(QC)lock | D7(QC)lock |

| A8(QC), A8' | A8(QC), A8' | A8(QC), A8' | A8(QC), A8' |

| A9 | A9 | A9 | A9 |

When it is B's turn, B can produce blocks based on A8.

If A8' reaches QC

The state of the last block of the four nodes is as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7(QC) lock | D7(QC)lock | D7(QC)lock | D7(QC)lock |

| A8, A8'(QC) | A8, A8'(QC) | A8, A8'(QC) | A8, A8'(QC) |

| A9 | A9 | A9 | A9 |

When it is B's turn, B can produce blocks based on A8'.

If neither A8, A8' reaches QC

Due to network reasons, different nodes receive different blocks, and C cannot receive any blocks. The state of the last block of the four nodes is as follows:

A B C D D7(QC) D7(QC) D7(QC) D7(QC) A8(B, A8'(D) A8(B), A8'(D) A8(B), A8'(D) A9 A9 A9 when timeout, view-change is triggered. At this time A may take two actions.

- A does not send ViewChange message

As honest nodes, B and D send ViewChange message according to the rules. C is down and cannot send ViewChange message.

A B C D nil(Byzantine) ViewChange<D7> nil(down) ViewChange<D7> The ViewChange cannot reaches QC. And the view can only switch to B normally after C failure recovers.

- A does send ViewChange

A B C D ViewChange<D7> ViewChange<D7> nil(down) ViewChange<D7> At this time, ViewChange can reach QC, and B can rotate normally and produce blocks based on D7.

View-change exception#

Assume that it is A's turn to produce block. A produce block 8 and 9 based on block 7. Block 8 and 9 are synchronized to B, C, and D. A receives enough PrepareVote messages for blocks 8 and 9. Block 8 and 9 reach QC state on A. However, due to network reasons, D did not receive enough PrepareVote messages for block 8, B, C and D did not receive enough PrepareVote messages for block 9. The block state of each node is as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7(QC)commit | D7(QC)lock | D7(QC)lock | D7(QC) |

| A8(QC)lock | A8(QC) | A8(QC) | A8 |

| A9(QC) | A9 | A9 | A9 |

When timeout, A, B, C and D will send ViewChange messages. B receives ViewChange messages as follows:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| ViewChange<A9> | ViewChange<A8> | ViewChange<A8> | ViewChange<D7> |

By rule, B should select A9 as HighestQCBlock from the 4 received ViewChange messages, and produce new blocks based on A9 and broadcast it to other nodes, carrying prepareQC of A9 and viewchangeQC.

However, B can completely abandon ViewChange <A9>, choose A8 as HighestQCBlock, and produce new blocks based on A8 and broadcast it to other nodes, carrying prepareQC of A8 and viewchangeQC. The blocks based on A8 can also be verified by other nodes.

If B is a Byzantine node, B may produce blocks based on both A8 and A9 to fork.

B synchronizes the blocks produced based on A8 and A9 to other nodes at the same time. If other nodes receive all new blocks at the same time:

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| D7(QC) commit | D7(QC)commit | D7(QC)commit | D7(QC)commit |

| A8(QC)lock | A8(QC)lock | A8(QC)lock | A8(QC)lock |

| A9(QC) B9:A8 | A9(QC) B9:A8 | A9(QC) B9:A8 | A9(QC) B9:A8 |

| B10:A8 B10:A9 | B10:A8 B10:A9 | B10:A8 B10:A9 | B10:A8 B10:A9 |

| B11:A9 | B11:A9 | B11:A9 | B11:A9 |

After consensus, there are three possible outcomes:

B8:A8 reaches QC

A B C D D7(QC) commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit A8(QC)lock A8(QC)lock A8(QC)lock A8(QC)lock A9(QC) B9:A8(QC) A9(QC) B9:A8(QC) A9(QC) B9:A8(QC) A9(QC) B9:A8(QC) B10:A8 B10:A9 B10:A8 B10:A9 B10:A8 B10:A9 B10:A8 B10:A9 B11:A9 B11:A9 B11:A9 B11:A9 At 9th height, the blocks A9 and B9: A8 only reached QC, and are not finalized, so the chain is not forked. When it is C's turn, C can produce new blocks based on A9 or B9: A8.

B10:A9 reaches QC

A B C D D7(QC) commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit D7(QC)commit A8(QC)commit A8(QC)commit A8(QC)commit A8(QC)commit A9(QC)lock B9:A8 A9(QC)lock B9:A8 A9(QC)lock B9:A8 A9(QC)lock B9:A8 B10:A8 B10:A9(QC) B10:A8 B10:A9(QC) B10:A8 B10:A9(QC) B10:A8 B10:A9(QC) B11:A9 B11:A9 B11:A9 B11:A9 When B10:A9 reaches QC, A9 is be locked, and A8 is commited. All nodes are in the same state, the chain is not forked. When it is C's turn, C can produce new blocks based on B10: A9.

B9:A8 and B10:A9 have not reached QC It may be caused by D network abnormality or D host downtime. At this point, the view-change is triggered. If B is a Byzantine node, B may or may not send a ViewChange message.

- B does not send ViewChange message

A B C D ViewChange<A9> ViewChange<A8> ViewChange<A9> nil In this case, C will produce blocks based on A9.

- B does send ViewChange message

A B C D ViewChange<9> nil ViewChange<9> nil The ViewChange cannot reaches QC. And the view can only switch to C normally after D failure recovers.

Review and Summary#

This article discusses the current common BFT-type consensus algorithms, and proposes a CBFT protocol that can be more suitable for the public network environment. It can greatly improve the speed of block confirmation and satisfy the blockchain on the premise of meeting safety and liveness. There is a growing need for consensus speed.

References#

[1] M. J. Fischer, N. A. Lynch, and M. S. Paterson, "Impossibility of distributed consensus with one faulty process," J. ACM , 1985.

[2] L. Lamport, R. Shostak, and M. Pease. The Byzantine Generals Problem. ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 4 (3), 1982.

[3] M. Castro and B. Liskov. Practical byzantine fault tolerance. In OSDI, 1999.

[4] E. Kokoris-Kogias, P. Jovanovic, N. Gailly, I. Khoffi, L. Gasser, and B. Ford, “Enhancing Bitcoin Security and Performance with Strong Consistency via Collective Signing,” 2016.

[5] TEAM T Z. Zilliqa TechnicalWhitepaper [J]. Zilliqa, 2017: 1–8.

[6] Guy Golan Gueta, Ittai Abraham, Shelly Grossman, Dahlia Malkhi, Benny Pinkas, Michael K. Reiter, Dragos-Adrian Seredinschi, Orr Tamir, Alin Tomescu, "a Scalable and Decentralized Trust Infrastructure", 2018.

[7] C. Unchained, “Tendermint Explained — Bringing BFT-based PoS to the Public Blockchain Domain.” [Online]. Available: https://blog.cosmos.network/tendermint-explained-bringing-bft-based-pos-to-the-public-blockchain-domain-f22e274a0fdb.

[8] M. Yin, D. Malkhi, M. K. Reiterand, G. G. Gueta, and I. Abraham, “HotStuff: BFT consensus in the lens of blockchain,” 2019.

[9] “EOS.IO Technical White Paper v2.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/EOSIO/Documentation/blob/master/TechnicalWhitePaper.md.

[10] Dan Boneh, Manu Drijvers, Gregory Neven. "BLS Multi-Signatures With Public-Key Aggregation", 2018.